It was on an early morning some time in 1837 that one of the biggest ‘Eureka’ moments in Indian history took place. The Brahmi script, an ancient Indian script that had for long flummoxed historians and researchers studying India's past, had finally been deciphered. Now, Indians could understand their distant past as never before. And the man who achieved this was an extraordinary Englishman named James Princep (1799-1840)

As the British empire began expanding across India following the Battle of Plassey in 1757, a number pf British writers, travelers, scholars, merchants and officials attempted to cross this line of shade to rediscover India's past. They were traversing newly conquered British territories to marvel and study the ruins of Khajuraho, Ellora and Madurai.

Prinsep's superior at the Calcutta mint was Horace Hayman Wilson (1786-1860), the most eminent Orientalist of his time. Wilson was a Sanskrit scholar, who had interest in Ayurveda and was the first person to translate Rigveda, the Vishnu Purana and Kalidasa's Meghaduta in English.

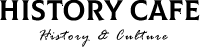

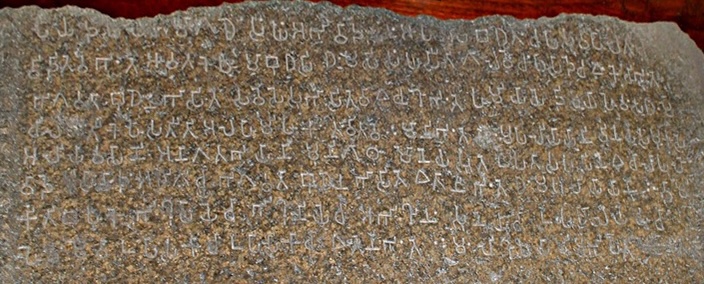

In Calcutta, Prinsep took over as editor of the Journal of the Asiatic Society, and solicited contributions from across British territories. Scholars had noticed that there were similar – in some cases identical – inscriptions on pillars and rocks in widely separated areas of India. Not a single living human understood the script in which they were written. Painstakingly, Prinsep collated all the available data and in 1837 finally decoded what we now call the Brahmi script.

The Brahmi inscriptions on pillars and rocks were in Prakrit language, a vernacular tongue rooted in Sanskrit. They had been commanded by a king who referred to himself as Devanampiya Piyadasi, Beloved of the Gods.

Some of Ashoka’s pillars in the far northwest of his empire were written in a second unknown script, now called Kharoshti. The same script appeared in coins from regions in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan, sometimes paired with legible Greek. Prinsep’s final accomplishment was the decipherment of Kharosthi. Since the script of the Indus Valley civilisation has not been deciphered, and because there is a break in the epigraphical record for over a 1,000 years after the collapse of that civilisation, the inscriptions he decoded remain the oldest comprehensible pieces of writing in India.

He said - Upon carefully comparing them [the three inscriptions] with a view to finding any other words that might be common to them, I am led to a most important discovery; namely all three inscriptions were identically the same.

Sadly, the heavy workload took a toll on Prinsep’s health. He kept working, despite poor health and died on 23rd April 1840 of a brain ailment at the age of 41. In 1843, the citizens of Calcutta built a memorial in his honour on the banks of Hooghly river, which is still called Princep Ghat.

While much of James Prinsep’s work remained incomplete, what he discovered would prove invaluable to future historians & archaeologists - he opened the entire chapters of Indian history.

© Yeshwant Marathe

yeshwant.marathe@gmail.com

#Brahmi #Ashoka #Prinsep #Kharoshti