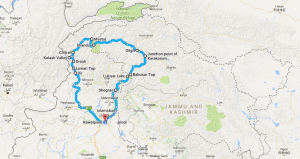

The Kalash are a Dardic Indo-Aryan indigenous people residing in the Chitral District of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Their population is currently estimated to be around 4000.

They speak the Kalasha language, from the Dardic family of the Indo-Aryan branch. They are considered unique among the people of Pakistan. They are also considered Pakistan's smallest ethnoreligious group and traditionally practice a religion that some authors characterise as a form of animism. At the same time, academics classify it as "a form of ancient Hinduism". During the mid-20th century, an attempt was made to put force on a few Kalasha villages in Pakistan to convert to Islam. Still, the people fought the conversion and, once official pressure was removed, the vast majority resumed the practice of their religion. Nevertheless, about half of the Kalasha have since gradually converted to Islam, despite being shunned afterwards by their community for having done so.

The Kalash are considered an indigenous people of Asia, with their ancestors migrating to the Chitral valley from another location, possibly further south. Some also believe them to have been descendants of the Gandhari people. The neighbouring Nuristani people of the adjacent Nuristan (historically known as Kafiristan) province of Afghanistan once had the same culture and practised a faith very similar to the Kalash, differing in a few minor particulars. The first historically recorded Islamic invasions of their lands were by the Ghaznavids in the 11th century. Nuristan had been forcibly converted to Islam in 1895–96, although some evidence has shown the people continued to practice their customs. The Kalash of Chitral has maintained its separate cultural traditions.

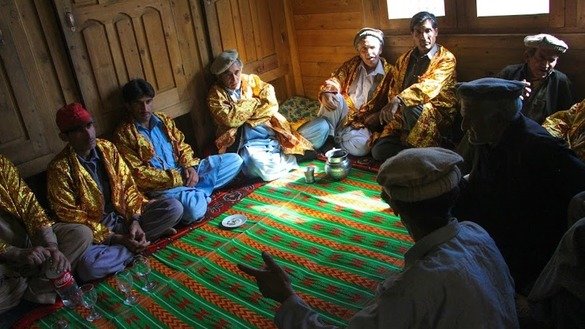

The culture of the Kalash people is unique and differs in many ways from the many contemporary Islamic ethnic groups surrounding them in northwestern Pakistan. They are polytheists, and nature plays a highly significant and spiritual role in their daily life. As part of their religious tradition, sacrifices are offered, and festivals are held to give thanks for the abundant resources of their three valleys. Kalasha Desh (the three Kalash valleys) is made up of two distinct cultural areas. The valleys of Rumbur and Bumburet form one, and Birir valley the other; Birir Valley is the more traditional of the two.

Kalash mythology and folklore have been compared to ancient Greece, but they are much closer to the Hindu traditions in other parts of the Indian subcontinent. The Kalash have fascinated anthropologists due to their unique culture compared to the rest in that region.

The Kalasha language, also known as Kalasha-mun, is a member of the Dardic group of the Indo-Aryan languages. Its closest relative is the neighbouring Khowar language. Kalasha was formerly spoken over a larger area in south Chitral, but it is now mostly confined to the western side valleys, having lost Khowar.

There is some controversy over what defines the ethnic characteristics of the Kalash. Although quite numerous before the 20th century, the non-Muslim minority has seen its numbers dwindle over the past century. A leader of the Kalash, Saifullah Jan, has stated, "If any Kalash converts to Islam, they cannot live among us anymore. We keep our identity strong." About three thousand have converted to Islam or are descendants of converts, yet still, live nearby in the Kalash villages and maintain their language and many aspects of their ancient culture.

Kalasha women usually wear long black robes, often embroidered with cowrie shells. For this reason, they are known in Chitral as "The Black Kafirs". Men have adopted the Pakistani shalwar kameez, while children wear minor versions of adult clothing after the age of four.

In contrast to the surrounding Pakistani culture, the Kalasha do not work in general separate males and females or frown on contact between the sexes. However, menstruating girls and women are sent to live in the "bashaleni", the menstrual village building, during their periods, until they regain their "purity". They are also required to give birth in the bashaleni.

The three main festivals of the Kalash are the Chilam Joshi in the middle of May, the Uchau in the autumn, and the Chaumos in midwinter.

The Kalash people are primarily practitioners of the traditional Kalash religion, which some observers label as animism. Still, others label it "a form of ancient Hinduism"; however, a sizeable minority has converted to Islam. According to Sanskrit linguist Michael Witzel, the traditional Kalash religion shares "many of the traits of myths, ritual, society, and echoes many aspects of Rigvedic religion". Kalash culture and belief system differ from the various ethnic groups surrounding them. Still, they are similar to those practised by the neighbouring Nuristanis in northeast Afghanistan before their forced conversion to Islam.

Their religion is a form of Hinduism that recognises many gods and spirits" and that "given their Indo-Aryan language, the religion of the Kalasha is much more closely aligned to the Hinduism of their Indian neighbours." It can also be termed as "a form of ancient Hinduism infused with old pagan and animist beliefs." In line with Ancient Hinduism, the Kalasha people believe in one God (known as Brahman in both the pre and post-Vedic periods) with reverence to minor 'gods' (Deva) or more aptly known as celestial beings. They also use some Arabic and Persian words to refer to God. Specific deities were revered only in one community or tribe, but one was universally revered is the ancient Hindu God Yama Râja called Imr'o in Kâmviri. Mahandeo is a deity whom the Kalash pray to and is known as Mahadev in other languages of the Indian subcontinent in modern Hinduism. There are several other deities, semi-gods and spirits. They live in the high mountains, such as Mount Kailash like Tirich Mir, but they descend to the mountain meadow in late autumn. There also is a general pattern of belief in mountain fairies Suchi (súči), who help in hunting and killing enemies, and the Varōti (called vātaputrī in Sanskrit), their violent male partners of Suchi, reflecting the later Vedic distinction between Apsaras and Gandharva. These deities have shrines and altars throughout the valleys, where they frequently receive goat sacrifices.

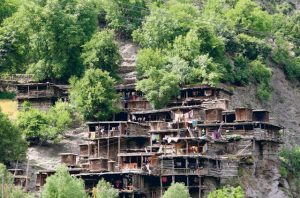

The region is highly fertile, covering the mountainside in rich oak forests and allowing for intensive agriculture, although most work is done not by machinery but by hand. The mighty and dangerous rivers that flow through the valleys have been harnessed to power grinding mills and to water the farm fields through ingenious irrigation channels. Wheat, maise, grapes (generally used for wine), apples, apricots and walnuts are among the many foodstuffs grown in the area, along with surplus fodder used for feeding the livestock.

Historically a goat herding and subsistence farming people, the Kalasha are moving towards a cash-based economy whereas previously wealth was measured in livestock and crops. Tourism now makes up a large portion of the economic activities of the Kalash. To cater to these new visitors, small stores and guest houses have been erected, providing new luxury for visitors of the valleys. People attempting to enter the valleys have to pay a toll to the Pakistani government, which is used to preserve and care for the Kalash people and their culture. After building the first jeepable road in the Kalasha valleys in the mid-1970, people are engaged in other professions like tourism and joining services like military, police, border force, etc.

Being a tiny minority in a Muslim region, some proselytising Muslims have increasingly targeted the Kalash. Some Muslims have encouraged the Kalash people to read the Koran so that they would convert to Islam. The challenges of modernity and the role of outsiders and NGOs in changing the environment of the Kalash valleys have also been mentioned as real threats for the Kalash.

During the 1970s, local Muslims and militants tormented the Kalash because of the difference in religion and multiple Taliban attacks on the tribe led to the death of many; their numbers shrank to just two thousand. The Kalash people are often referred to as Kalash Kafirs by the local Muslims and have been subjected to increasing killings, rape and seizure of their lands. As per the Kalash, forced conversions, robberies, and attacks endanger their culture and faith. Kalasha gravestones are desecrated, and the symbolically carved horses on Kalasha altars are destroyed.